Society has some job advice for you: do something you’re passionate about.

Yeah, I’ve heard it before too, and in the words of Miranda Priestly:

Feeling fulfilled by your work is certainly not a bad thing. Let’s be real, the work we do as speech-language pathologists is deeply rewarding… and that is something I like about my job.

But passion is more than just feeling fulfilled. Passion suggests that you’ll do “whatever it takes” for your job and your clients. That isn’t healthy and it can make you vulnerable to exploitation.

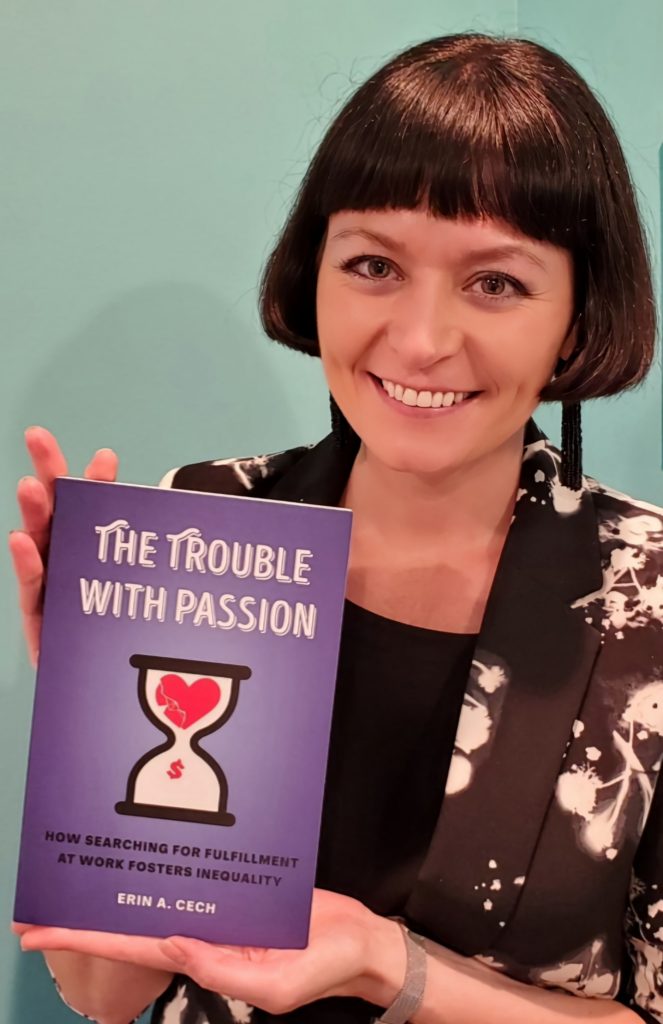

Don’t take my word for it (not that you’d need to considering you’ve probably experienced it yourself!), Dr. Cech is a sociologist and associate professor at the University of Michigan who has been studying this “passion principle.”

She published a new book, The Trouble with Passion: How Searching for Fulfillment at Work Fosters Inequality (links to Amazon). In it she discusses pursuing passion at work, and what it really means when you put passion before fair pay and working conditions. I’ve taken info from her book and a few interviews she’s done for this post.

Has it always been this way?

Historically here in the United States, people didn’t focus on passion at work. Cech shares that in the 1940’s and ’50s ‘stability’ and ‘earning enough for your family’ were the most important thing from a job. In the 70’s and 80’s, it was ‘self-expression’.

But after a few decades of stagnant wages, outsourcing, dismantlement of unions and workers’ rights, the job market is a pretty bleak place. So, most college-educated workers began thinking, “Well… I’m going to be overworked and underpaid… so I might as well like it!”

Praising Passion is Rewarding Privilege

Steve Jobs gave a commencement speech at Stanford back in 2005. He highlighted the role he believes passion should play in work saying, “The only way to do great work is to love what you do. If you haven’t found it yet, keep looking. Don’t settle.”

Jobs and many other tech moguls tout their stories of dropping out of college and pursuing their passion for an idea that changed the world and made them wildly wealthy. These narratives romanticize passion.

But let’s be real, that kind of success is not guaranteed.

Cech says, “The stories of the Mark Zuckerbergs and Steve Jobs have cultural relevance because they are success stories,” Cech says (emphasis added).

Nobody talks about people who follow their passion and fail.

So, where does the privilege part come in?

First generation college students and those from disadvantaged backgrounds (i.e., people of color, children of immigrants, those with chronic health issues, folks from rural areas, etc.)are less likely to have any safety net in place to fall back on if they fail.

So? They don’t take the risk.

Further, they probably don’t have access to vast and affluent social networks to leverage when they are in a position to risk it all.

Cech’s research says that people from affluent families are more likely to have jobs that speak to their passions and are stable and well compensated, compared with people from less wealthy backgrounds.

Passion Can Lead to Exploitation

Cech is pretty clear here, so I’m just gonna quote her directly, “People motivated by passion first are more likely to work harder than people who aren’t personally invested in their work. But they aren’t necessarily paid any more.”

Employers want passionate workers for their dedication, but also for something else. Cech says, “they expect that people who are passionate about their work will put in more work without demanding an increase in pay.” (emphasis added).

Does this sound familiar to any of my SLPeeps out there?

It frustrates me when an SLP says, “I don’t do this for the money…”

Why?

It seems to me like using your values to justify poor compensation. If my employer stopped paying me, I would stop working. And I’m guessing so would a lot of other people.

Does that mean money is my only reason for working as an SLP and that I’m a greedy person?

Certainly not. However, it does mean that I’m not only expecting but in need of a certain level of compensation to sustain my ability to work.

Promoting Passion at Work Doesn’t Mean Better Outcomes

As speech-language pathologists, we all know the kind of hours and effort we put in to our shared mission of improving the quality of life for people with communication and swallowing disorders. And we’re not the only kinds of employees putting in this kind of effort. I’m looking at you teachers…

But sometimes “passion” becomes confused with overwork.

And that leads to burnout and resentment.

“It’s one thing to be kind, considerate, helpful and attentive [at work]. And it’s another thing to perform that work as though that’s the soul or core piece of one’s identity,” says Cech.

Uncoupling your sense of dedication from “putting in extra hours,” is actually a benefit to you, your boss, and your clients in the long run.

Why?

“When we give workers more rest, more control over their schedule, more vacation time, they’re actually more productive, they’re more resilient, they’re more creative,” says Cech. She goes on, “it’s actually not to an organization’s benefit to demand this culture of overwork all the time, even though there seems to be a logical connection between expectations of passion and productivity.”

Passion Is Not Competence

My Dad worked most of his life as a plumber. He was incredibly skilled at it, with numerous specialty certifications allowing him to work in sensitive places like surgical suites and government buildings.

But was he passionate about it?

Not really. He did it because he was good at it, and it provided a good salary to support his family.

To this day, he finds deep pride in pointing to a hospital or school and saying, “I built that,” or in being able to teach me how to maintain my home (he saved me so much money showing me how to replace my own waterheater!).

He is passionate about his family and experimenting with bbq sauce recipes, not about fitting pipes.

We need to remember that as SLPs our competence does not come from our passion.

Our competence (and in my opinion our value to clients) comes from our training, our ability to read and apply research to our practice, critical thinking, problem solving, a commitment to constantly learning.

So, what do we do about it?

Passion at work hasn’t always been a cultural priority.

You can be good and effective at your job without it being your passion.

Instead of getting all your zest for life from one place, Cech advises “diversifying your meaning-making portfolio.”

Or in other words, seek meaning and fulfillment from other activities.

Ask yourself: What things excite me outside of work? And then figure out how to cultivate those things.

I get my zest for life from my family, spending time in nature, day dreaming, and playing around with technology (like this blog).

In the comments below, share some of the ways you pursue passion outside of work.

I quit my job. Now I am lost as to what to do. I am an awesome SLP & very good at my job, but they burnt me out. Why would I ever go back to such torture? For a salary that pays me half of what I am worth with my knowledge base? Why encourage people to do something they no longer love? Happiness is success, not money. Keep rolling out new SLPs, I guess. This is an exercise in futility.

Wow! That’s a big deal. First, congratulations for getting out of what I’m guessing was a toxic work environment. That couldn’t have been an easy thing to do. Second, I agree that happiness is not money, but I’m not sure about happiness = success. I think that’s tough with so many ways to define success. Finally, can I ask, was there something you were looking for in this post that you didn’t find? Wishing you all the luck in whatever comes next.