As Speech-Language Pathologists, we spend a lot of time working with people disabilities. And it is easy to get caught up in our day to day tasks and forget to see the proverbial ‘forest for the trees’.

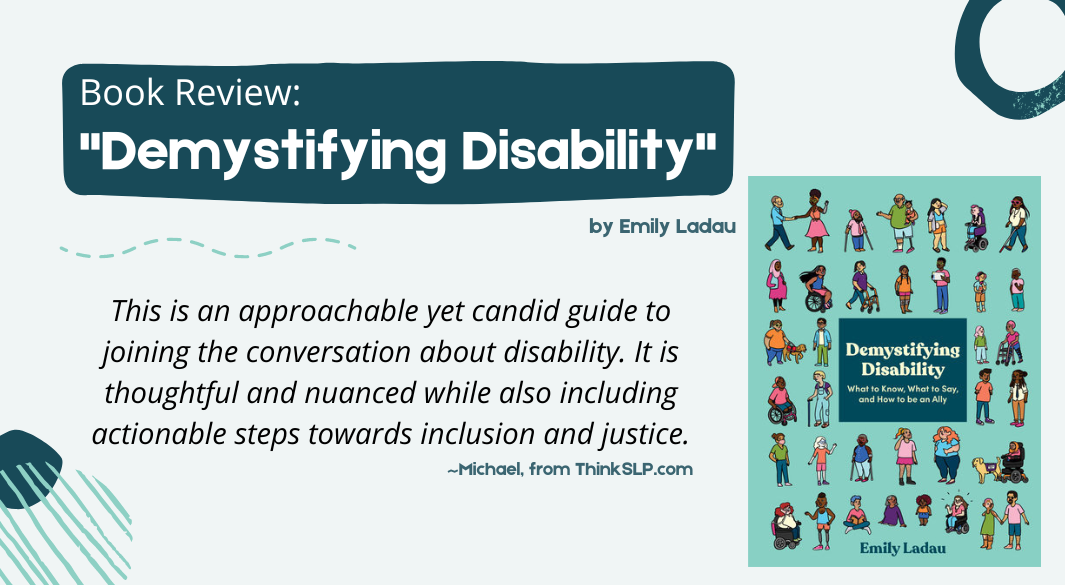

I picked up Emily Ladau’s book Demystifying Disability as a way to remind myself of my broader role as an advocate for people with unmet communication and swallowing needs while also broadening my understanding of disability as part of a whole person.

In the end, I have come away with a better understanding of disability as part of the broad continuum that is human experience. Emily explains it all sincerely but with a light-hearted tone that lowers your defenses so the message sinks in.

In this article, I’m going to walk you through my thoughts on the book in a few different parts

- The Cover

- The Content: Chapter by Chapter

- Some Critiques

- My Conclusions

- My Commitments as an Ally & Accomplice

Before we jump in, I’d like to mention that some links below are no-cost affiliate links to Amazon.

The Cover:

I think Ms. Ladau’s book is absolutely worthy of being judged by its cover.

Its artwork is a thoughtful prelude to the diverse coverage of disability contained within. The 37 characters on the front cover, just like the real people they represent, have unique bodies with different sizes, colors, shapes, and ways of moving through and existing in the world. Like the words within, the front cover leaves room at the table for nearly everyone.

After you the read book and get to know a bit about how Emily sees the world, you realize that Tyler Feder was a brilliant choice of illustrator to accompany Emily’s book. Her work (on this book and others) embraces big feelings, feminism, trauma, mental health, the diverse human body, and pop culture. Truly, the cover is a work of art with a message and commentary all of its own that perfectly compliment Emily’s work.

One thing that I was curious about is the choice of the ‘medical green’ for the background – a color that is also used thematically inside the book. I wonder if Tyler or Emily would even call it “medical green”? Or if they had a different rationale for choosing the color. I’m no art critic, but (after reading Eli Claire’s Exile and Pride), I have thought a lot about the medical model for understanding disability, and I wonder if this green color was a conscious decision to lean into that model, an attempt to redefine it, or something else entirely.

Update: I reached out to Emily via email. She kindly explained that green is simply her favorite color. Look at me #over_thinking_it.

The Content:

Ladau’s work contains 6 titled chapters, preceded by an introduction and followed with a soft roar to action at the end.

- Introduction: Why Do We Need to Demystify Disability

- Chapter 1: So, What Is Disability, Anyway?

- Chapter 2: Understanding Disability as Part of a Whole Person

- Chapter 3: An (Incomplete) Overview of Disability History

- Chapter 4: Ableism and Accessibility

- Chapter 5: Disability Etiquette 101

- Chapter 6: Disability in the Media:

- Conclusion: Calling All Allies and Accomplices

The Introduction: We Do We Need to Demystify Disability

I found Ladau’s perspective on disability advocacy and the need to ‘demystify disability’ very much aligned with my personal perspectives. So, know that bias.

One of the first things I underlined when I read the book was this gem on page three, “If the disability community wants a world that’s accessible to us, then we must make the ideas and experiences of disability accessible to the world.” Looking back at it after reading the entire book, I see how vulnerable Emily made herself in taking this position.

Ladau goes on to explain how this isn’t an easy thing to do and it isn’t always a popular position (more on that in the critiques below). And when you read the book, the author lives up to those nuances by sharing moments when she struggled to live up to her own philosophy.

Chapter 1: So, What is Disability Anyway?

While the title question of the chapter is only briefly addressed, I think Ladau is still successful in communicating that there is not a single, perfect, static definition for disability. The author even humbly and adroitly acknowledges that her experience is not universal and so includes varying definitions of disability from other disabled people. The chapter includes thoughts on disability from other people with disabilities. In doing this, the author is practicing what she’s preaching in her conclusion when she says “Pass the Microphone.”

Kudos Emily.

Segue: as I use the term ‘disabled people’ (rather than ‘people with disabilities’), I’d like to share that the remainder of the chapter (and book) discusses how to talk about disability including a rich and nuanced discussion of person-first vs identity first language as well as sections thoughtfully explaining the problematic nature of “functioning labels” (e.g., high vs low functioning).

When I finished reading Chapter 1, my only unmet expectation was about models for understanding disability, which I thought went hand in hand with defining disability. I was pleasantly surprised to find this covered quite directly in Chapter 2.

Chapter 2: Understanding Disability as Part of a Whole Person

Emily’s opening words set the perfect tone, “My relationship status with disability is complicated.” Playful but at the same time deeply true, this opening illustrates that disability can be a part of one’s identity but at the same time it is a relationship (i.e., unique and dynamic).

As Emily goes on to discuss her relationship with disability, she introduces the concept of intersectionality and ‘people whose multiple identities overlap.’ It is a powerful concept that is integral to understanding disability.

I was expecting models of disability in chapter 1, but thankfully they’re covered in chapter 2. Emily gives an overview of the medical model, which is probably the most prevalent today. Importantly, she goes on to discuss 6 other models or lenses through which disability can be viewed. None of these is discussed in-depth but (like most of the book), introduce the reader the concept and invite them to learn more. As a side note, Exile and Pride by Eli Claire has a much deeper but equally human perspective on models for disability.

Chapter 3: An (Incomplete) Overview of Disability History

This was probably one of the most impactful chapters for me. Before this, I hadn’t studied much Disability History. Sure I learned things in graduate school about historical perspectives and practices, but always in a roundabout way. And in my work now, I’m obviously living and working within the context history has left us. But I’d never looked in depth at the historical antecedents.

Emily’s “(incomplete) overview of disability history” focuses on the 20th century in the United States. Emily moves quickly covering the ‘highlights’ but even those are enough to have encouraged me to learn more about the past and what’s going on right now.

Given how very recent much of the ‘history’ is, I was able to find several Youtube videos and news stories of the events Emily covered. I encourage you to do the same as you read.

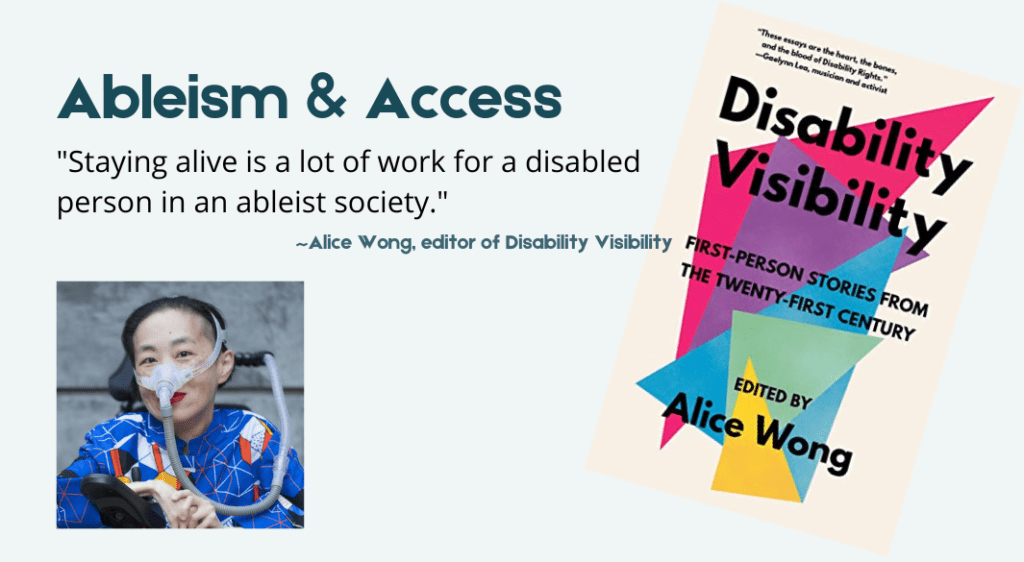

Chapter 4: Ableism and Accessibility

In this chapter, Emily offers a powerful and far reaching definition of ableism:

“Ableism is attitudes, actions, and circumstances that devalue people because they are

disabled or perceived as having a disability.”

~Emily Ladau in Demystifying Disability

The power in this definition is that it goes beyond just actions to include the more insidious forms of discrimination and prejudice that exist. Emily includes “attitudes” which are intangible and often invisible. She also includes “circumstances” which alludes to the systemic nature of many -isms.

As Emily puts it, “To most of society….[ableism doesn’t] raise any red flags because [it’s] woven into the fabric of everyday life, simply accepted as the norm.” The chapter goes on to share Emily’s personal experiences as well many others ranging from systemic examples to countless individual interactions.

One thing I love about Emily’s writing is that she is vulnerable and introspective rather than confrontational. This is especially apparent in chapter 4. At one point she writes, “We all need to check ourselves to make sure that we’re not holding on to ableist ideas and biases.” And when Emily writes, “we” she is actually including herself.

Take for example Emily’s confession a few lines earlier, “As hard as I fight against ableism, there have most definitely been times when I’ve been ableist toward other disabled people. And it’ll likely happen again… ” She doesn’t flinch as she admits her own past shortcomings.

This transparency and willingness to admit her own mistakes sets Emily’s writing and work apart from others. She does not preach from a pedestal. Rather she is conceding her own faults and reflecting alongside the reader. Emily’s work is rooted in introspection.

Chapter 4 ends with a brief examination of accessibility. And in this, Emily once again holds space for a broad spectrum of experiences, disabilities, and ultimately diverse people living diverse lives.

Chapter 5: Disability Etiquette 101

If you’re expecting a concrete list of “Do’s and Don’ts” then Chapter 5 is for you!

When explaining her suggested Do’s and Don’ts, Emily patiently assumes the best of intentions and then thoughtfully outlines how to live out that intention in a way that is respectful and dignifying to both parties.

You might read some of the advice and find yourself thinking… “Well isn’t that obvious?” And I would agree. But Emily kindly yet firmly reveals these etiquette rules that are hidden in plain sight. And I’m here for it.

Chapter 6: Disability in the Media:

In the process of reflecting on Emily’s book, I realize that Chapter 6 kind of brings it all together.

In a now familiar pattern, Emily starts this chapter with her own experience. She explains what it has meant to her seeing herself in the media. In the bulk of the chapter, Ladau describes harmful representations of disability in the media. She makes plain the underlying assumptions, biases, and stereotypes that underpin them. In the end, she briefly discusses the positive portrayals as well, sort of bringing the discussion back to where it started.

Conclusion: Calling All Allies and Accomplices

In concluding, Emily ends with several logical calls to action. It starts with her discussion of allyship as a “more of a ‘show, don’t tell’ kind of thing (which I’m totally on board with). Emily takes a few lines to distinguish between “ally” vs “accomplice,” which to be frank, didn’t seem necessary to me. But, hey… it’s Emily’s book, and in the name of allyship/accomplice-ness, I’m trying to learn more about this.

I’m getting off track.

In brief, this conclusion has some really great next steps to take. Some are concrete and others are just as important but a little less tangible. This is definitely a part of the book I plan to revisit a few times.

Some Critiques

In preparation for this article and in digesting Emily’s work, I read reviews online of her work – some from the comments section of Amazon and Goodreads, and others like this article on NPR (I love NPR so much).

As I sorted through reviews, I came up with a couple common critiques that I thought I’d address:

She’s ‘Too Nice’

Several reviewers seemed to accuse Emily of being ‘too soft’ in her approach to educating people and debunking ableism. It seems those reviewers were expecting something more pugnacious. And I’ll agree that Demystifying Disability is not quarrelsome, but I don’t think that makes it any less fierce.

In fact, I think Emily’s tone throughout the book is a strength of the work.

The Book Is Ableist

Another common critique is that the book is suggesting an ableist route to achieving disability rights. It seems the critics are referring this idea on page 3: “If the disability community wants a world that’s accessible to us, then we must make the ideas and experiences of disability accessible to the world.”

The critics are suggesting (entirely correctly) that the value of disabled person does not come from their willingness nor ability to tell their story, especially not to non-disabled people. I get that, and I agree. A disabled person doesn’t owe anyone any kind of explanation or justification for existing.

That said, I also agree with Emily. I think hearts and minds is where change needs to happen. I think people are deeply emotional and respond on a primal level to stories with which they connect. And there is no one better to tell the story of disability than someone who is living it.

So, is it fair? Nope. Is it a way forward? Sure.

I will add, it isn’t the only way forward. Like one critic pointed out (and Emily discussed in her book), there are other ways of calling attention to disability rights, educating people, and bringing about meaningful change.

“It’s One Person’s Experience”

Several reviewers point out that Emily draws on her own experiences heavily in the book. And for some reason, they think that’s a bad thing. I don’t see why. She does it openly and transparently, and more importantly she explicitly draws attention to the fact that her experience is not universal – creating and holding space for others. Also, she literally ends the book with, “Now, keep going.” More than inviting the reader to hear more stories, think more, learn more, do more… she’s ordering it!

I suppose that if you look at this book as a potential textbook or primer, the reliance on personal experience can be problematic. But I think excluding personal narratives from discussion of disability runs the risk of dehumanizing and decoupling the conversation from the immediate realities that people with disabilities face.

My Conclusions

Overall, I found Ladau’s work to be thoughtful, intelligent, and accessible.

My favorite thing about Emily’s work, and what I think is most powerful as well, is that she calls for introspection rather than judging others. For example her chapter on disability etiquette isn’t some decontextualized laundry list of do’s and don’ts or a broad permission to throw stones at those who aren’t ‘woke.’ With each suggestion comes a rationale that asks the reader to check their own biases and fears – to do the real work.

To be clear, Emily (and I!) also wants you to accompany that introspection with meaningful action. But something I think many of us forget when we’re discussing improving the situation for marginalized populations is the ‘fight for hearts and minds.’ In my opinion, that is what really helps to bend Dr. King’s ‘moral arc of the universe toward justice’.

My Commitments

A book like Emily’s isn’t to be read and put back on the shelf. One because of the beautiful cover art. And two, because it should compel you to act.

And so in that spirit of action, I’ll close with a few commitments I made to myself as I read:

- Do my part in my making my website (www.thinkSLP.com) more accessible.

- Learn more about the history of disability rights (any book recommendations?).

- Pass the microphone: Find opportunities to lift up and amplify the perspectives of those people who should be centered rather than my own (I’m gonna start with learning about student-led IEP meetings).

- Better understand being an ally vs being an accomplice.

What are you going to do?

In the comments below, on Facebook or Twitter, let me know what you are going to do as an ally and accomplice to people with disabilities.